Michael Smith’s 1990 theatrical production revisited

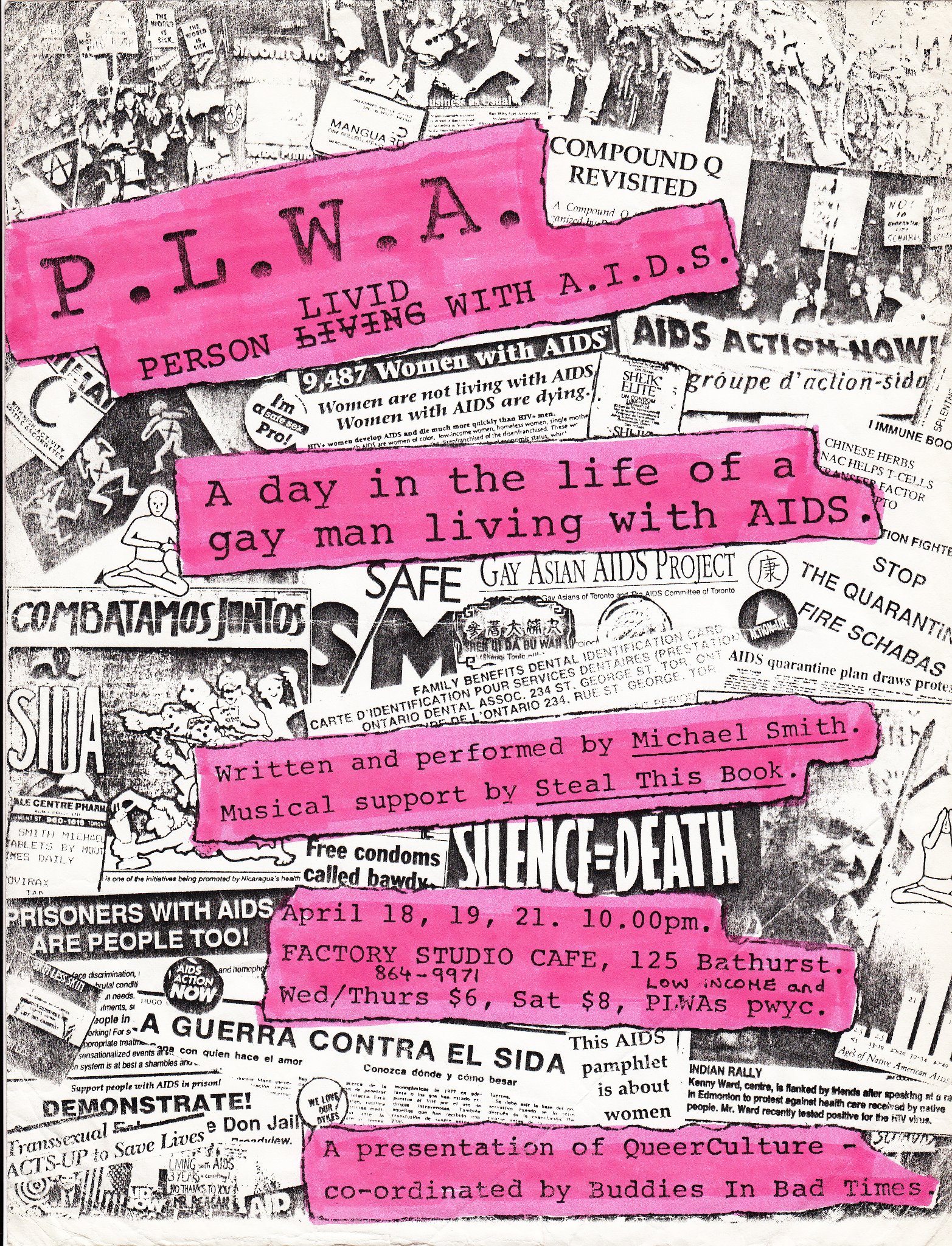

Michael Smith’s 1990 one-man show with occasional musical accompaniments was performed as part of the QueerCulture Festival organized by Buddies in Bad Times before Buddies became the anchored institution it is today. Person Livid With AIDS: A Day in the Life of a Gay Man Living with AIDS (PLWA), which had a three day run at the Factory Studio Café at Bathurst and Adelaide (a precursor to today’s Factory Theatre), was also captured on a grainy video tape that recently resurfaced through the efforts of British Columbia-based sex worker activist Andy Sorfleet.  The tape was found in the estate of deceased Toronto lesbian activist Chris Bearchell who had retired to the Gulf Islands of British Columbia.[1] While the production would be restaged in early 1991 as a fundraiser for AIDS ACTION NOW! and Gays & Lesbians of the First Nations,[2] this tape, in all its fuzzy, glitchy, VHS glory, along with an accompanying publicity poster, and ‘zine, is primarily what remains of Smith’s original play.

The tape was found in the estate of deceased Toronto lesbian activist Chris Bearchell who had retired to the Gulf Islands of British Columbia.[1] While the production would be restaged in early 1991 as a fundraiser for AIDS ACTION NOW! and Gays & Lesbians of the First Nations,[2] this tape, in all its fuzzy, glitchy, VHS glory, along with an accompanying publicity poster, and ‘zine, is primarily what remains of Smith’s original play.

Smith, a British transplant, was a well-known queer Toronto anarchist whose activist work extended well beyond HIV/AIDS activism. He was organizing with AIDS ACTION NOW! (AAN!) from its emergence in the late 1980s and was instrumental in laying the groundwork for what would later become the Prisoners’ AIDS Support Action Network (PASAN) as a member of AAN!’s prisoner subcommittee. Smith was remembered in memorial in AIDS ACTION NOW!’s newsletter as a defender of not only gay rights and rights of people living with HIV/AIDS, but also of women’s rights, native peoples’ rights, and animal rights. He is also remembered fondly in the oral histories recorded by the AIDS Activist History Project as a member of the anarchist urban homestead collective Kathedral B and a member of the radical faeries, an international queer anti-establishment counter-culture that embraces spiritualism over the commercialism and misogyny of mainstream gay culture.

PLWA was written and produced in the context of socially conservative austerity governments in power across Canada (Mulroney), the UK (Thatcher), and the US (Reagan and Bush) from the outset of the epidemic in the early 1980s to the early 1990s when PLWA was staged. During this period AIDS-related deaths continued to climb at devastating rates while government health agencies dragged their feet acknowledging the existence of the epidemic let alone implementing provincial and federal AIDS treatment and prevention strategies. The promised effective treatments from researchers and pharmaceutical companies on the horizon never materialized until half a decade after PLWA, and well over a decade after the first recorded case of AIDS in Canada in 1982. HIV quarantine laws had been discussed and proposed provincially across Canada, including the 1990 proposal by Ontario’s then Chief Medical Officer of Health Richard Schabas to classify HIV as a virulent disease and therefore legitimizing the use of quarantine of sexually active HIV+ people.[3] The first criminal prosecutions for HIV exposure began in 1989, paving the way for Canada’s present day sordid reputation for being a world leader in criminal prosecutions for HIV non-disclosure per capita.[4]

Despite the bleak picture painted here, where there is oppression, there is also resistance. Smith organized with the newly formed activist group AAN! in 1988, Toronto’s answer to New York city’s AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), a similar American activist group founded just a year prior. In 1989 AIDS activists from all over the world, led by members of ACT UP/NYC, AAN!, and the Montreal-based Réaction-SIDA, helped take over the opening ceremony of the Fifth International Conference on AIDS in Montreal.[5] This watershed moment in AIDS activism helped solidify the now taken for granted axiom that people living with a disease are experts of their own experience and must be given the opportunity to take an active role in shaping the fight against the disease.[6] On June 28, 1990, just two months after the staging of Smith’s PLWA the Canadian government would finally release its first national AIDS strategy after years of intense pressure from AIDS activists across the country.[7]

Returning to Smith’s PLWA, it’s worth noting a number of aspects of the production to situate it within a genealogy of cultural resistance. Most obvious is the instructive nature of PLWA, fitting into the long tradition of Brechtian theatre that aims to educate its audience.[8] Smith instructs his audience in safer sex practices and offers a testimonial snapshot into what a day in the life of a person living with AIDS might look like. From demonstrating the quotidian yet irksome tasks of scheduling multiple doctor’s appointments a day and swallowing pills every few hours, to the emotional devastation wrought by stigma, government neglect, and the spectre of an early death. Smith also goes further, exhibiting an intersectional HIV/AIDS politics that acknowledges and analyzes Smith’s own privileges in society as a white gay man with AIDS from a middle-class family while also foregrounding the concerns of women, First Nations people, drug users, poor people, homeless and unhoused people, and prisoners affected by HIV/AIDS. This demonstration of intersectional politics foreshadows the coming political schisms that would fracture AIDS activist organizations in the United States, and to a lesser degree in Canada, in the early 1990s.[9]

Returning to Smith’s PLWA, it’s worth noting a number of aspects of the production to situate it within a genealogy of cultural resistance. Most obvious is the instructive nature of PLWA, fitting into the long tradition of Brechtian theatre that aims to educate its audience.[8] Smith instructs his audience in safer sex practices and offers a testimonial snapshot into what a day in the life of a person living with AIDS might look like. From demonstrating the quotidian yet irksome tasks of scheduling multiple doctor’s appointments a day and swallowing pills every few hours, to the emotional devastation wrought by stigma, government neglect, and the spectre of an early death. Smith also goes further, exhibiting an intersectional HIV/AIDS politics that acknowledges and analyzes Smith’s own privileges in society as a white gay man with AIDS from a middle-class family while also foregrounding the concerns of women, First Nations people, drug users, poor people, homeless and unhoused people, and prisoners affected by HIV/AIDS. This demonstration of intersectional politics foreshadows the coming political schisms that would fracture AIDS activist organizations in the United States, and to a lesser degree in Canada, in the early 1990s.[9]

Aspects of Smith’s production can also be understood as therapeutic. While drama therapy now occupies a place within the walls of research institutes and universities, activist cultural interventions precede the academic interest by decades. Smith’s vignette where he delivers an angry diatribe to a mannequin onto which he projects the personhood of then Minister of National Health and Welfare Perrin Beatty, concludes with an emphatic “Fuck off ass hole!” and a long scream. This cathartic release, accompanied by a complete disrobing in order to “unleash the naked truth,” is met with whoops and clapping from the audience. This cathartic release shared between Smith and the audience in the imagined verbal take down of a callous politician makes obvious that those occupying the theatre’s seats are likely friends and fellow activists equally fed up with government inaction on HIV/AIDS.

Aspects of Smith’s production can also be understood as therapeutic. While drama therapy now occupies a place within the walls of research institutes and universities, activist cultural interventions precede the academic interest by decades. Smith’s vignette where he delivers an angry diatribe to a mannequin onto which he projects the personhood of then Minister of National Health and Welfare Perrin Beatty, concludes with an emphatic “Fuck off ass hole!” and a long scream. This cathartic release, accompanied by a complete disrobing in order to “unleash the naked truth,” is met with whoops and clapping from the audience. This cathartic release shared between Smith and the audience in the imagined verbal take down of a callous politician makes obvious that those occupying the theatre’s seats are likely friends and fellow activists equally fed up with government inaction on HIV/AIDS.

Smith’s performance of self for others is also of interest in PLWA. Following the theoretical work of the late performance studies scholar Jose Muñoz on the ethics of self and working on the self for others, Smith’s production provides a vivid example on what a performance of self for others could look like in the Canadian context.[10] While Muñoz’s work focuses on the public performance of self by AIDS activist and reality TV personality Pedro Zamora from the Real World San Francisco, Smith’s performance of self runs parallel. In PLWA Smith performs as himself, taking different parts of his lived experience and stitching them together into a digestible hour and a half production. Smith’s performance of self is a testimony to his lived experience and activism at the height of the AIDS crisis, sacrificing his privacy to demonstrate his reality and his intersectional political response to a broader public. A public that was not only reached through this live theatrical experience, but also through a thirty-minute condensed version that was produced for the cable television series Toronto: Living With AIDS[11] as well as a number of additional abbreviated performances Smith did while touring the United States with the Emma Goldman Gypsy Players, a precursor to the radical faerie theatre troupe the Eggplant Faerie Players.[12] This group would later script their own version of PLWA based on the life story of a close friend of Smith’s named SPREE who was inspired by Smith’s work.[13]

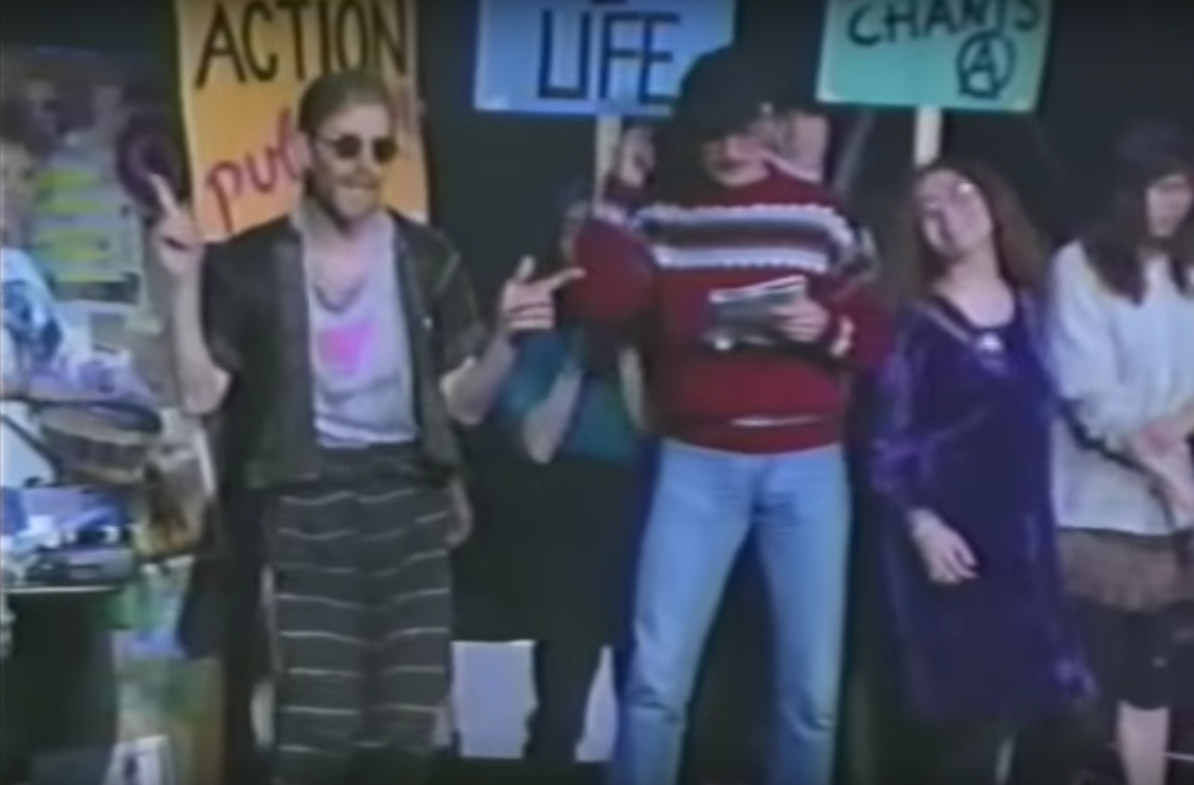

Thinking about the shift between the live theatrical event of PLWA, the VHS videotape that captured the performance on magnetic tape, and the digital video file that has now been made publicly available via Youtube through the AIDS Activist History Project is also important for thinking about the afterlife of the original event. Media studies scholar Alexandra Juhasz and others have noted that the emergence of the AIDS crisis also coincided with the emergence of consumer grade video recording technologies like the camcorder that was used to record PLWA.[14] Jean Carlomusto and Gregg Bordowitz discuss what looking at video tapes of activist demonstrations feels like in his 1993 short Fast Trip, Long Drop. In an editing suite Carlomusto and Bordowitz discuss the changing meaning of activist video tapes as time passes and more and more of their friends and comrades depicted in the videos they’ve made have died. While Smith’s production is largely a one-man show, the musical interludes with the band Steal This Book of which he was a member as well as the sing-songy group demonstration scenes are filled with members of the Toronto activist scene and cultural milieu. Here we get a vibrant sense of the collective character of his life and activism, but watching the video from today’s vantage point can be particularly painful for many who were close friends of Smith. He died after a series of debilitating bouts of AIDS-related illnesses less than a year after the first staging of PLWA. Likewise, others who joined Smith on stage during these musical ensembles are also no longer with us, and both Smith’s and their absence today changes the meaning of these moving images.

Thinking about the shift between the live theatrical event of PLWA, the VHS videotape that captured the performance on magnetic tape, and the digital video file that has now been made publicly available via Youtube through the AIDS Activist History Project is also important for thinking about the afterlife of the original event. Media studies scholar Alexandra Juhasz and others have noted that the emergence of the AIDS crisis also coincided with the emergence of consumer grade video recording technologies like the camcorder that was used to record PLWA.[14] Jean Carlomusto and Gregg Bordowitz discuss what looking at video tapes of activist demonstrations feels like in his 1993 short Fast Trip, Long Drop. In an editing suite Carlomusto and Bordowitz discuss the changing meaning of activist video tapes as time passes and more and more of their friends and comrades depicted in the videos they’ve made have died. While Smith’s production is largely a one-man show, the musical interludes with the band Steal This Book of which he was a member as well as the sing-songy group demonstration scenes are filled with members of the Toronto activist scene and cultural milieu. Here we get a vibrant sense of the collective character of his life and activism, but watching the video from today’s vantage point can be particularly painful for many who were close friends of Smith. He died after a series of debilitating bouts of AIDS-related illnesses less than a year after the first staging of PLWA. Likewise, others who joined Smith on stage during these musical ensembles are also no longer with us, and both Smith’s and their absence today changes the meaning of these moving images.

This video is just one testament to the resilience and creativity of queer HIV-positive people in the face of structured abandonment by the very governments that are supposedly there to defend and care for its people. Much like the way photographs functioned during the Holocaust as a technology of cultural memory, the videotapes of activist cultural interventions by HIV-positive people during the deadliest period of the AIDS crisis serve as a vivid rejoinder against forgetting how the battles against HIV/AIDS were fought. And not just to not forget, but to remember that our queerest gifts, creativity and humour, can be wielded to fierce and fabulous ends.

—

Ryan Conrad is an activist, artist, and scholar from a mill town in central Maine. He is a Research Associate with the AIDS Activist History Project and a Ph.D. candidate at Concordia University in Montréal.

Notes

[1] It is thought that Chris Bearchell herself shot this video documentation of PLWA, but it has yet to be corroborated without a doubt.

[2] Darien Taylor, George Smith, and Bernard Courte, “In Memoriam: Dan Wardock, Ross Laycock, Michael Smith,” AIDS ACTION NEWS!, March 1991, 4.

[3] For a snapshot of the provincial and national media see: “Quarantine AIDS Victims Some Bar Officials Argue,” The Gazette, October 1, 1985; “B.C. Proposal would Allow Quarantine of AIDS Victims,” The Gazette, July 9, 1987; “N.S. Minister Proposes Bill to Quarantine AIDS Carriers,” Toronto Star, September 23, 1988; Ashley Geddes, “Province Expands AIDS Quarantine to Include Carriers,” Calgary Herald, December 9, 1988; Christie McLaren, “Chief Medical Officer Urges AIDS Quarantine,” The Globe and Mail, February 8, 1990; “N.B. Editorial Suggesting Quarantine for Victims Fuels AIDS Debate,” The Gazette, July 17, 1990.

[4] Eric Mykhalovskiy and Glenn Betteridge, “Who? What? Where? When? And with What Consequences? An Analysis of Criminal Cases of HIV Non-disclosure in Canada,”Canadian Journal of Law and Society, Volume 27, no. 1, 2012, 31–53.

[5] See the AIDS Activist History Project’s Montreal-based interviews for a thorough reflection on organizing the activist response to the Fifth International AIDS Conference.

[6] Ron Goldberg, “Conference Call: When PWAs First Sat at the Table,” POZ Magazine, July 1, 1998.

[7] Kelly Toughill, “Dramatic Change in the Politics of Canada’s Fight Against AIDS,” Toronto Star, July 10, 1990.

[8] For a detailed analysis on Brecht’s “Learning Plays” see: Douglas Kellner, “Brecht’s Marxist Aesthetics: The Korsch Connection,” in Bertolt Brecht: Political Theory and Literary Practice, ed. by Betty Nance Weber and Hubert Heinen (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1980) 29-42.

[9] While tension existed within AAN!, where some members pushed for more open democratic processes and more intersectional activism within AAN!, the organization survived and continues to be active to this day. The acrimonious split between ACT UP/NYC and Treatment Action Group (TAG) in January 1992 on the other hand, contributed in part to ACT UP/NYC’s dissolution. For a detailed account of the rise and fall of ACT UP see: Deborah Gould, Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s Fight Against AIDS (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

[10] José Esteban Muñoz, “Pedro Zamora’s Real World of Counterpublicity: Performing an Ethics of Self,” in Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999) 143-60.

[11] John Greyson, “Interview with John Greyson,” Telephone interview by author, September 23, 2016.

[12] SPREE, “Interview with SPREE,” Skype interview by author, October 16, 2016.

[13] For a more detailed look at SPREE and the Eggplant Faerie Players’ version of PLWA see: Ezra Berkley Nepon, Dazzle Camouflage: Spectacular Theatrical Strategies for Resistance and Resilience (Philadelphia: Self-published, 2016).

[14] Alexandra Juhasz, AIDS TV: Identity, Community, and Alternative Video (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995).