Originally posted on Media Co-op (Sudbury)

Recovering the history of direct action AIDS organizing in Canada

by Scott Neigh

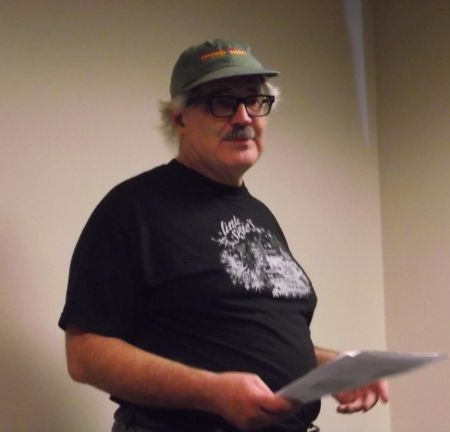

Scholar and activist Gary Kinsman of Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario, introducing the film *United in Anger: A History of ACT UP* and talking about the new AIDS Activist History Project that he is working on with Alexis Shotwell of Carleton University in Ottawa. SUDBURY, ON — It was an era when rage and creativity won life-saving victories. Neglected by governments, scorned by much of the public, and facing rapid illness and death, in the mid-1980s people living with HIV/AIDS and their supporters began taking radical direct action in cities across North America. Yet this history is in danger of being forgotten.

Scholar and activist Gary Kinsman of Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario, introducing the film *United in Anger: A History of ACT UP* and talking about the new AIDS Activist History Project that he is working on with Alexis Shotwell of Carleton University in Ottawa. SUDBURY, ON — It was an era when rage and creativity won life-saving victories. Neglected by governments, scorned by much of the public, and facing rapid illness and death, in the mid-1980s people living with HIV/AIDS and their supporters began taking radical direct action in cities across North America. Yet this history is in danger of being forgotten.

Earlier this week, the screening of a film about the New York chapter of the direct action AIDS group ACT UP served as the first public event in Sudbury, Ontario, for a new project seeking to recover some of that radical history in the Canadian context. The work is being spearheaded by Alexis Shotwell, a sociologist at Carleton University in Ottawa, in collaboration with Gary Kinsman of Laurentian University in Sudbury.

At the event, Kinsman said, “Our most important objective is to make sure this history is not lost, not forgotten.” For him, the point is not only remembering for its own sake, but remembering “what people accomplished” through organizing collectively, as well as “the importance of direct action politics in what they accomplished.” The work done by this movement across the continent “changed the course of history.”

The research will involve doing in-depth interviews with people who were participants in that organizing between the mid-1980s and mid-1990s in Halifax, Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, and Vancouver. While scholars involved in the project may also write papers and books based on the findings, the main product of the research will be a website aimed at the general public that will house the interviews and other material in a way that is hoped to become an accessible community and movement resource.

The work is still in its early stages. They are currently building partnerhsips with organizations in the cities in question, including Aids Action Now and the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives in Toronto. Part of this process involves finding out what research has already been done locally, as well as determining how many of the organizers from that period — many of whom were living with HIV at the time, in the era before many treatment options were available — are still alive. Kinsman said, for instance, that he had the chance over the summer to see a photo of the founders of the Halifax People With AIDS Coalition, and all but two of them have now passed away.

Direct Action

Direct action is the use of tactics that will have an immediate material impact to reveal, oppose, or address a social problem, including strikes, sit-ins, occupations, and property destruction. This is often posed in contrast with approaches to political action that are mediated by formal political mechanisms, and also with more purely symbolic approaches — though direct action, particularly as practiced in the AIDS movement, has often combined powerful theatricality and sybmolism with its more direct impacts. For the research in Canada, Shotwell and Kinsman will be using a very broad understanding of direct action.Actions portrayed in the film, United in Anger: A History of ACT UP, focused on governments that were fatally slow in responding to AIDS, drug companies that profited from the illness and were not responsive to people’s needs, and other powerful institutions that perpetuated harmful policies. An early and persistent focus of the organizing in the film was on speeding the process of drug development in order to save lives, and on pushing research and regulatory regimes to become more open and particpatory. ACT UP also took many actions related to lack of access to healthcare due to poverty, and to research practices and regulatory definitions that marginalized women, people of colour, and poor people who were infected.

Kinsman said that their preliminary research indicates that direct action organizing began in Canada a little later than in the US, and that in many places it had a somewhat different form and focus. There seems to have been less use of tactics like political funerals and grassroots media production in the Canadian context, for example. And while the inadequate response of governments and for-profit drug companies was still a crucial issue, in a number of cities in Canada there were other groups already focused on questions related to treatment. This meant, for instance, that the Vancouver group was able to focus on (successfuly) opposing a provincial proposal at the time to quarantine all people who were infected. A pivotal moment continent-wide in winning concessions from medical and regulatory authorities was the 1989 direct-action takeover of the opening plenary of the Fifth International AIDS Conference in Montreal by activists from Montreal, Toronto, and the US.

Unfortunately, the research will not be focusing on Sudbury. Kinsman said, “My understanding, and I’d love to be proven wrong, is that there was basically none of this kind of AIDS activism” in the city.

The project is also trying to connect their historical work with ongoing struggles by people living with the disease. A key issue in Canada at the moment is the criminalization of the sexual behaviour of people living with HIV/AIDS. Canada, Kinsman said, has “one of the highest rates of incarceration of HIV+ people in the world” for reasons connected to their infection status, and has among the most oppressive laws in this area.

The event in Sudbury was co-sponsored by the Sudbury Coalition Against Poverty, an anti-poverty group that emphasizes direct action in its work. Kinsman said that when it comes to that approach to politics “there’s an awful lot to be learned and to be inspired about” in the history of the AIDS movement, for groups working in all kinds of areas.

In the words of a woman interviewed in the film while she was in the midst of a direct action, “When we act up, we get what we’re demanding. When we’re silent, we don’t.”

Those wishing to contact the AIDS Activist History project can do so at aidsactivisthistory@gmail.com.

Scott Neigh is the author of two books of Canadian history told through the stories of activist from Fernwood Publishing, and the producer/host of Talking Radical Radio.